Antinous everywhere!

|

|

By

Michael Thompson

Rome is a wonder of

archaeological and artistic heritages. Some might visit St. Peter's

for one kind of spiritual inspiration. But gay travelers are likely

to feel different connections and resonances. What remains of

pre-Christian Rome is a window onto older concepts of sexuality, and

an alternative aesthetic. The relation of the Church to that prior

legacy is complex and conflicted.

A visit to almost any

Italian museum reveals that the ancients didn't equate nudity with

a lack of modesty. Gods, emperors, athletes, warriors, and noblemen

could embody ideals of human perfection without the artifice of

garments. As had the Greeks, from whom they inherited so much,

ancient Romans revealed man without reserve. Manifestations of this

comfort with the male form are found in marble all around the city.

The Vatican Museum (Viale

Vaticano 13), paradoxically, is home to one of the world's most

amazing collections of nude male beauty, diverse as to time and

place. The Church wasn't always so tolerant. Fourth-century

Christian emperors looked the other way when roving mobs led by

monks looted and destroyed temples, particularly in the countryside,

and countless statues of incredible beauty were shattered. More than

a millennium later, with the old pagan religions safely dead, a more

confident Church (following the fashions of the political elite)

commissioned new works inspired by these same artifacts.

During the

remarkable 15th century, the finest artists of their time were

employed by patrons such as the Medici family of Florence, who also

contributed four popes. As the West emerged from the "dark ages"

it looked back to the old Roman empire as a cultural beacon. Much as

local gods and sacred places of conquered peoples had been

incorporated into Roman pagan religions, so too the temples,

institutions, holidays and aspects of the Roman gods had been

quickly assimilated into the new Christian milieu. Eventually much

of pagan art was also accommodated. The sexual proclivities of some

church superiors seem often to have made them sympathetic at crucial

times in this transition.

The Vatican complex

includes the Museo Pio Clementino with its 54 galleries, and the

tour here ends with Michelangelo's masterpiece at the Sistine

Chapel. Postures and knowing looks so faithfully captured by the

master artist betray his affection for the street youth and urchins

who portray the angels and saints, intact with the grit and grime

they brought with them as models (and likely bedmates). Through him

they transcend humble origins, and bridge the millennia, recalling

fragments of an older world we can no longer fully comprehend, when

the divine could guilelessly assume mortal flesh.

Spare some time

also for other halls, including Museo Chiaramonti, Museo Gregoriano

Etrusco, and Museo Egiziano, with their ancient Roman, Greek,

Etruscan and Egyptian materials. Get a head start from the Vatican

Museum's website (Mv.vatican.va), which offers extensive virtual

tours.

Other worthwhile

destinations include the Borghese Gallery (Piazzale del Museo

Borghese 5; Galleriaborghese.it), with examples from the works of

Caravaggio, Bernini, Canova, Rubens, Raphael, Titian, and many

others from the collection of Cardinal Scipione; and the Capitoline

Museums (Piazza del Campidoglio 1, atop Capitoline Hill;

Museicapitolini.org) which ranges over ancient art and architecture.

In Rome, you don't have

to stay indoors to savor magnificent art. The Fontana delle

Tartarughe in the Piazza Mattei depicts four youths, one at each

corner, each astride a porpoise with turtles above. The fountain

dates from 1588, and was restored and modified in 1658. You'll

find this tiny square just off Via Arenula, near the tranquil

courtyard of the Palazzo Mattei di Giove, which is adorned with

antique statues, busts, and bas-reliefs, and home to the Italian

Center for American Studies.

The Villa of Hadrian (Via

di Villa Adriana 204) was the emperor's retreat to the northeast

of the city, now in Tivoli. that includes the greatest Roman example

of an Alexandrian garden. The Spanish-born Hadrian was also

responsible for the building of the Pantheon and the wall that bears

his name that protected Roman Britain from parts north. Hadrian was

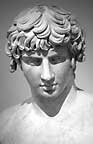

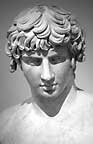

the lover of Antinous, whom he made a god after the youth's death.

Antinous represents a Roman ideal of youthful beauty, and his visage

survives in countless busts and coins as perhaps the most common

among extant portrayals of any face from the ancient world.

But many ancient

cults left few relics and scant information. It would be fascinating

to know more. In Greece and Rome, sex could be sacred, and bodies

were regarded more holistically, before concepts such as sin and

pornography profaned them with divisions of good and evil. About

Mithraism, for instance, little is known except that it was popular

with soldiers, exclusively male, celebrated underground, and

involved intense initiations. The cult of Apollo was close to

official ideals of the Roman state, but it was complemented by

now-lost rites and rituals honoring Bacchus and Dionysus.

Such mysteries and

ecstasies could be celebrated in temples and public festivals. Some

famous marbles and paintings, if wrought today, would verge on the

illegal. One wouldn't want to gloss over some brutal aspects of

Roman society, but their civilization had characteristics we might

envy.

The dissonances are

instructive. Stone endures only a little longer than flesh in terms

of the ages, but unless intentionally broken, long survives film

negatives or digital files. One trusts these ancient artworks will

outlast our own age to inspire unimaginable futures.

You are not logged in.

No comments yet, but

click here to be the first to comment on this

Magazine Article!

|